Ch. 8

After what felt like an eternity, Isocrates finally came to, and was racked by the worst fit of coughing yet. The torch had burned itself out, but it was no longer needed; the light of the morn shone, as proof he slept through the night. The sedative he took worked exactly as was promised, but it was not what he had in mind; nay, far from it. Who would deliberately subject themselves to such agony? – a nightmare is bad enough, without playing on repeat.

Stripe had fallen asleep on the floor, in the same spot where he had sat keeping watch, but the hacking was like a clarion call. Even after Isocrates was back to breathing normally, he lay there awhile, in a state of utter shock. But eventually, he did regain self-control – and presence of mind – enough to rise, and get his day going. He opened the door, and headed out, with Stripe leading the way, like an overly excited tour guide.

Isocrates did feel lighter on his feet, but it would take more than a single night to fully recuperate. And just one had proved to be overwhelming; there would be no more sedatives for him, any time soon. The ringing in his ears was not quite as bad, either; there were as many crickets, but now they were chirping from further off.

Euandros emerged, from a lesser corridor, “I thought that I heard you moving round.” He said on approach.

“I didn’t mean to cause you to stir.” Replied Isocrates.

“You didn’t; Nae and I have been up for a while now – we even crept out at dawn, and said some words before your father’s barrow. We heard Stripe baying, and assumed we woke you.”

“If he was barking, I didn’t hear it. Whatever my sister gave me, put me down.”

“I knew that it would.” Euandros replied. “You should try it with a bit of wine.” He added, with a glint in his eyes.

Isocrates’ thoughts, were that he would pass.

From up ahead, Stripe barked, so as to remind Isocrates that he was there – with somewhere to be. Isocrates took the hint, and gestured for Euandros to follow him. Together, they set after the hound.

The trip through the hall, ended up being a walk of shame; the tapestry reminding Isocrates of his rash behavior. Euandros left the matter alone; Isocrates was glad for as much, and hurried on past. Stripe was already waiting for him by the exit; as soon as he cracked it open, the dog bolted out. Standing there in the open doorway, he got a better sense of the time; the sun was higher up than he would have guessed.

“I didn’t know I slept that long.” He said in surprise.

“And you very obviously needed it.” Euandros remarked. “I was hoping, that you might be up to do some fishing.”

“I don’t see why not.”

“Capital; I brought my lucky pole.”

“Should I go get ready, then?”

“Not yet, we should eat, first.” Said Euandros.

Isocrates nodded in agreement. He actually had his appetite back, so after so long a fast, a meal sounded wonderful. Closing the door behind him, he and Euandros made for the andron; they found Carnaea already there.

“I take it, you’re well aware that the kitchen shelves are empty.” She stated, although it was in the form of a question.

Now, in all honesty, that detail had slipped Isocrates’ mind.

“I wasn’t expecting any company.” He said in defense.

“But there’s nothing there.” She reiterated.

“I only just ran out of supplies.” He explained – leaving out the part about his recent guests, of course. “I still have a sack of wheat in the cellar, though it will need to be ground.”

“But we should not live off bread alone.” She replied, staring at her brother, as if he should well have known better. “By chance, we’ve a little food left, from what we packed for the trip here; Philetos is preparing it, now. But I don’t know what will sustain us later, aside from some bread.” She said the last part derisively.

“Gods willing, we’ll have some fish to go with our fresh loaves.” Euandros interjected.

“Some fish from where?” Carnaea asked.

“I was planning on searching in the river; I hear that that’s where they like to hide.” He replied, grinning at her cheekily.

She did not seem amused.

“I don’t remember discussing any fishing plans.” She complained.

“You mean I can’t go?” He asked, becoming dejected.

“I didn’t say that, but there are far more important matters at hand.”

“What’s more important than fishing?”

“We just discussed the fact that there is wheat that needs grinding.” She replied.

“But isn’t that why we have Philetos?” Euandros inquired.

For the record, Isocrates thought he had a point.

“Philetos is getting on his years, and Agapetus isn’t here to offer his assistance.” Responded Carnaea.

“Philetos can manage, on his own.” Said Euandros, stubbornly.

Upon hearing this, Carnaea scoffed.

Just then, Philetos arrived, and he was carrying a tray of foodstuffs, that left much to be desired. It mostly consisted of week-old bread, and some salted beef, which reminded Isocrates of the mutton-strips. Fortunately, they did have some olive-oil, which helped soften up the bread – once it had long enough to soak. Isocrates set aside a few strips for the absent Stripe, although, chances were, the dog was getting along. While they sat and ate, Philetos quietly stood by, fetching drinks and such, whenever called upon.

As Carnaea indicated, the servant’s best years were long behind him; his hair and beard had almost no black remaining. While he was thin, he was upright, as opposed to his being hunched over, which oft occurs after a lifetime of servitude. It did not take the diners long to ingest the continental ariston; no one was full, but it beat a blank. Philetos set about clearing the table, and gathering the leftover scraps, which were his share.

“I guess we might as well be off to the blasted cellar, for the grain.” Said Euandros, still in a huff.

“Is something the matter, master?” Philetos inquired, sensing the shift in temperament – an important part of his skillset.

“Tis nothing.” Said Euandros, his lower lip poking out.

“You can’t lie to me.” Philetos pressed.

“Well, if you must know, Isocrates and I had plans on taking our poles out.” Came the longing reply.

“But, don’t let me keep you, master;” Philetos protested, “I can handle what is necessary.” He added with stolid confidence.

“Good man.” Said Euandros, cheering up; the servant’s assurance having revived his mood.

“Yay, but you don’t have to do it all by yourself.” Carnaea replied, rising from her own seat, and helping collect the dishes.

“He said he can manage, love.” Euandros reminded her.

She gave him a firm stare, and his shoulders sank.

* * *

Isocrates brought the sack of grain up from the cellar, and handed it over to Philetos to carry from there. It was a good-sized bag, with some weight to it; Philetos slung it over his shoulder, and then set about his way. Euandros was also present, and he was still crestfallen – Isocrates wondered why he did not put his foot down. He was not a scrawny man, the type that one might expect to cower often, nor did he come across as effete.

He was only slightly older than Carnaea, meaning, in his prime, so it was no case of elder abuse either. And he was respected in his community – outside of his home – as a monarchical deputy, he had connections. He could have had any woman, more or less, yet he chose Carnaea. Isocrates was glad that he never fell in love. Stripe was in the area, but he knew a bag of grain when he saw one, and as such, his focus was elsewhere.

Now up above, the sun was quickly gaining altitude; a few wispy clouds drifted by, but the sky was mostly clear. Notus was particularly active – even for that time of year – the hems of their garments were aflutter. But the breeze only served to recycle the humidity; the heat index was still in the red.

They went after the servant, heading for the mill, a structure built of rough stone, that stood beside an empty silo. The silo would soon get put to use though, as several of his neighbors would be squaring their debts with wheat. They entered the mill, which was a wide-open space, with several windows for ventilation – and light, since torches were restricted. The only furnishing was a sturdy looking table, set against a wall, and a saddle quern.

Philetos went and dropped his burden onto the table, and turned to face his assistants, “Can one of you open this?” He asked.

Isocrates was reaching for his knife, but Euandros got his out first, and proceeded to slice open the bag.

“Let’s get this work over with, that we might have some time left to play.” Said Euandros, resheathing his blade.

“If worse comes to worse, and we do run out of time, can’t we just go fishing on the morrow?” Isocrates asked.

“How I do wish that leisure was mine.” Euandros replied. “When I received the news of your father’s passing, I had another trip planned – one in an official capacity. Delegates from every region, still in opposition to Hypatos’ designs, are convening for a summit in Melitaea. Of course, I had to see that Nae made it here, to pay her respects, and to pay mine, but still, duty calls.”

“Pardon me, masters;” Philetos cut in, “with there being three of us, and just the one quern, it seems that we’ll have to take turns – who wants to go first?” He asked, and no one said anything.

Philetos sighed, and grabbed a handful of grain.

“What was I saying, now?” Euandros asked.

“Something about a prior engagement, in Melitaea.” Isocrates reminded him.

“Ah yes; a meeting of the minds, or should I say the mindless, for where they’ve gotten us, thus far.”

“I take it that you speak to the war effort; I heard that we’re past the point of trying to negotiate.”

“Whatever you heard, it’s worse; the threat has been downplayed.”

“And what is the truth, then?” Isocrates asked.

“Hypatos’ territory continues to expand; he recently added Coronaea to his long list of conquests. Now it’s just a matter of time, until he rolls into Phthia.”

“What of the men that we’ve stationed north of here?” Isocrates asked, now having to speak up, as Philetos had begun the very noisy act of grinding.

“It won’t be enough to stop the onslaught.” Euandros replied, his expression quite grim.

“I was one of the few who thought negotiations might have been prudent.” Said Isocrates, shaking his head.

“It’s far too late now.” Euandros replied.

“But how did it come to this? “

“Blame the fiend who calls himself the Lord of Vultures; only a villain would be so demented.”

“How do you plan to stop him?”

“The plan is to get together, and have a robust discussion.” Euandros replied. “I just wanted a day by the water, to relax, and to unwind, before being subjected to an assemblage of blowhards.”

“Then, what’s stopping you from going?” Isocrates asked.

“You heard what Nae said; she wants me to stay and help Philetos.”

“And who wears the chiton in the relationship?”

Euandros winced, as it clearly was not him.

“Just go grab your pole; what can Carnaea do to stop you?” Isocrates pressed.

“Trust me; you don’t want to be on her bad side.”

“It seems as if you’re already there.” Said Isocrates.

“You’re making more of it, than it is;” spoke Euandros flippantly, “we still might make it out of here today. How are we coming, so far?” He called over to Philetos.

“We’re getting there, master.” Came the strained response.

“Very good.” Euandros replied.

“Who cares if he gets finished, or not?” Isocrates railed. “Just tell Carnaea that you’re going fishing – and go. Or, better yet, don’t tell her anything; just get your pole, and I’ll get mine, and we’ll leave.”

“It’s best that I say something, at least.”

“Then you will?” Isocrates asked, rather surprised – he had begun to think that it was a lost cause.

Euandros stood there a moment and pondered, then seemed to make up his mind, and stormed out the mill. While his tortured in-law was off, reclaiming his manhood, Isocrates was left contemplating what he just learned. He still was ambivalent regarding Hypatos’ aims; rather than a loyalist, he considered himself a patriot. As long as the self-proclaimed Tagus stayed out of Isocrates’ affairs, then he could not care less.

Philetos continued drudging over the saddle quern, grinding the golden kernels into flour – the wind always caught some. A dust-cloud had taken over, and not just the air; it settled everywhere, like unto snowfall. After a brief interlude, Euandros returned, sans fishing pole.

“What did she say?” Isocrates asked.

“That we can’t go.” Euandros replied, back to moping.

“Don’t say ‘we’; I can come, and go as I please.”

“Well, I’m stuck here, till the wheat has all been ground.”

“You weren’t supposed to ask; you were supposed to tell her you were going.”

“I told her I wanted to, but she wouldn’t budge.”

“If you don’t stand up to her, she’ll keep running over you.”

“You might be correct.”

“I’m certain I am.” Isocrates said frankly.

“Then what should I do?”

“Let’s go fishing.”

“You mean, to Hades with Nae?” Euandros asked.

“Exactly.” Responded Isocrates.

“Come hither, Philetos; I need you to do me a small favor.” Euandros beckoned.

The servant hurried over, seemingly glad for the chance to take a break.

“What is it, that you require?” Philetos asked, with dust caked on his face and his arms, where it had stuck to the sweat.

“I need you to go get Nae’s attention, and to act as a distraction.” Euandros explained.

“How long do I need to keep her occupied?”

“Only for a short while, but make sure that you dust yourself off first, that you don’t go tracking flour through the house.”

“Understood.” Said Philetos, who then took his leave.

“What’s that about?” Isocrates asked, both curious and confused.

“Our trip is still on, as planned.” Euandros replied.

“But why is Philetos being sent as a diversion?”

“To give me time to sneak in, and steal away with my pole.”

With that, Euandros set off, as if the plan made sense.

* * *

Upon Euandros’ insistence, Isocrates also acted in secret, though he felt ridiculous burglarizing his own premises. He understood that if his sister saw him with his pole, the game was up, so he begrudgingly went along. While executing the operation, Euandros also found the time to secure his wineskin, as well as some cups. With Philetos in place, it was easy enough to pull off the heist, and to escape with Carnaea being the none the wiser. Stripe was no accomplice, but he was guilty by association, willingly taking part in the getaway.

Isocrates led them to the nearest pond, nestled in the foothills; a walk of only a few kilometers. The cicadas were desperate, with this being their final season; every tree they passed resounded with an unseen choir. A familiar musky scent, alerted the travelers that they were nearing their destination, and soon they arrived.

Prior to his enlistment, Isocrates had spent a lot of time there; the pond looked much smaller to him now. Just off the path leading in, several folk were fishing already; Isocrates recognized them all as neighbors of his. They recognized him too, and without saying anything, each of them gathered up his gear, and then left.

“Well, that was odd.” Spoke Euandros. “Some people don’t like to share.”

Isocrates was not about to explain.

“Better for us; we have the place to ourselves.” Euandros added, handing a cup over, and filling both.

He took a sip, and set about preparing his pole.

For bait, they collected grasshoppers, which were so plentiful that soon they had more than they would probably even need. They barely had their hooks in the water, before Euandros got a hit. A struggle earned him a large bream.

“I told you, this pole is lucky.” He bragged, unhooking the fish, and placing it on a stringer. “I got it at Lake Copais – have you ever been?”

“I haven’t made it there yet, but it’s on my to-do list.” Replied Isocrates.

“You won’t be disappointed; I caught an eel there once, that was this big.”

Euandros stretched his arms out to illustrate; Isocrates smelled horse shit.

They spoke about many things, as they stood and shot and breeze; the only topic that was forbidden was politics. Euandros brought in a second bream, bigger than the first, then a mid-sized perch, which was still a good catch. Isocrates inspected his hook, and noticed that his bait was missing; he replaced it, and tried again.

Euandros caught several more bream, and a few crappie. Isocrates thought he had something – it ended up being a sandal. They both got a kick out it though, pun intended; by that point, they were into their second cup. Euandros had caught another bream, and was baiting his hook for more, when, of a sudden, Isocrates had action. Whatever it was, seemed to put up a good fight, but when he got it on land, it was the size of a dormouse.

“If you keep at it, you’ll get a real bite soon.” Euandros offered.

Isocrates snatched another grasshopper.

To make a long story short, the only bites he got were from mosquitoes; he could not catch a bream, or a break. He was disappointed, but it only angered him slightly; the trip was not for him – the wine helped him come to that conclusion. Euandros lamented that the skin was almost empty; by Isocrates’ estimation, it had stretched pretty far.

Although the heat persisted, the sun had begun to set, Isocrates recommended that they should be heading in. The cicadas had given up, for the day, but Isocrates heard crickets in their stead, that might have been real. He also heard the faint sound of barking, and looked up to see that Stripe had made his way clear to the opposite side of the pond.

“Get back over here!” Isocrates shouted out.

Stripe heeded, in a literal sense – jumping in, and swimming cross. Isocrates sighed, but he was used to the behavior; Euandros burst out laughing – again, it could well have been the booze. Isocrates knew that he had had a few too many, and asked Euandros was he all right.

“Certainly.” Came the response, though it was in between hiccups.

The poles were gathered up; Euandros also made sure to grab his bountiful stringer, and they set their sights back for Othrys.

* * *

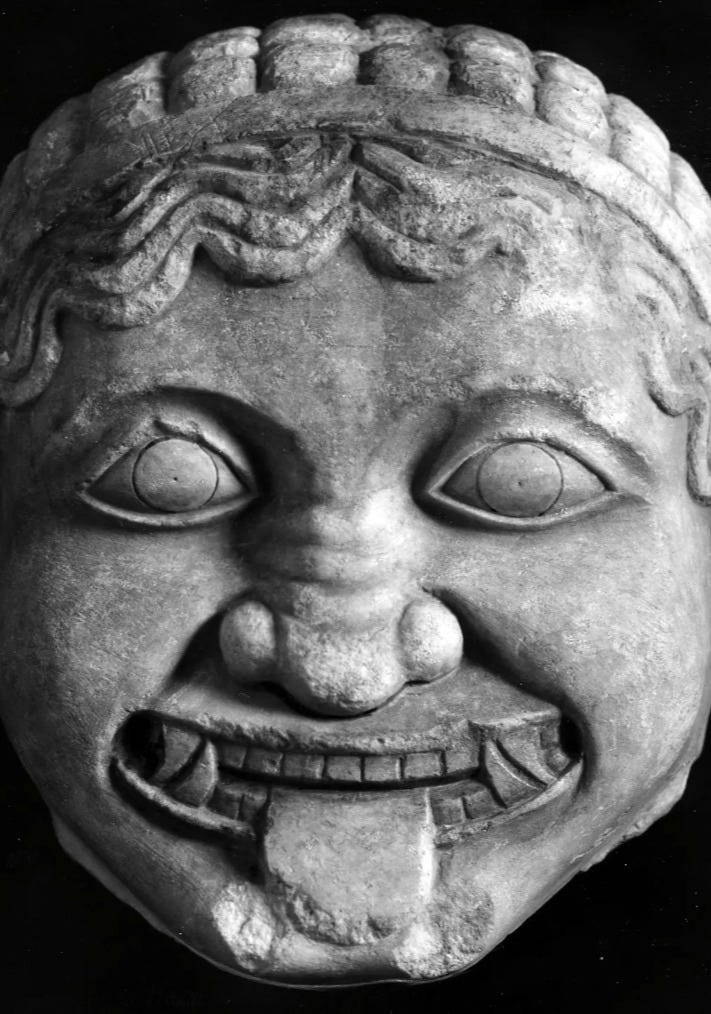

The sun had completely disappeared, by the time they made it back, and stumbled through the front door. Carnaea was waiting in the hall, standing with her arms akimbo, glowering like she was the fourth Gorgon. Isocrates was no expert on the female mind, but he was certain Stripe would have some company in the doghouse.

Of course, he was not the one who was in the hot seat, so he sidled by the tiny, but immovable object. Stripe followed suit – even he was slinking – and Euandros was forced to face the executioner, on his own. As Isocrates headed off, he heard the shrill admonition, that he knew was coming, ensue behind him and it was brutal. He was somewhat remorseful, in that he felt partially responsible, and he hated to leave a man behind.

(to be continued…)

Become a paid Subscriber, to access the entire vault, or Buy Me A Coffee, to support my work…